Detecting Active Tuberculosis Bacilli on TB Smears: A Nightingale Open Science Dataset

Authors: Yusen E. Lin1,2, Nick Foster3, Nathan Juergens3, Senthil Nachimuthu3, Josh Risley3, Katy Haynes3, Ziad Obermeyer3,4

1 Wellgen Medical

2 National Kaohsiung Normal University

3 Nightingale Open Science

4 University of California, Berkeley

Lead Nightingale analyst: Nick Foster

When using this resource, please cite: more options

Yusen E. Lin, Nick Foster, Nathan Juergens, Senthil Nachimuthu, Josh Risley, Katy Haynes, and Ziad Obermeyer. 2023. Detecting Active Tuberculosis Bacilli on TB Smears: A Nightingale Open Science Dataset. DOI:https://doi.org/10.48815/N5H59PAdditionally, please cite: more options

Sendhil Mullainathan and Ziad Obermeyer. 2022. Solving medicine’s data bottleneck: Nightingale Open Science. Nature Medicine 28, 5 (May 2022), 897–899. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01804-4

The Problem

Tuberculosis is one of the leading infectious causes of death worldwide [1]. Each year, millions of individuals contract and develop active TB without knowing [2]. Case identification and treatment are the primary methods for controlling spread as there is no effective TB vaccine for adults. Unfortunately, delays in diagnosis are common, especially in resource-limited settings, and can worsen individual outcomes and perpetuate transmission of the disease [3,4]. Recently, global TB control has been severely impacted by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care systems, and mortality from TB is on the rise for the first time in over a decade [5].

Despite recent advances in genomic testing, the pillar of diagnosing active pulmonary TB remains microscopy for the identification of mycobacterium tuberculosis in the respiratory sputum [1]. This requires microscopists with the time and training to accurately review all suspected cases of TB, which may not be routinely available in rural or developing nations. Automated digital microscopy has been proposed as a cost-effective solution [6,7]. An automated algorithm that could reliably detect mycobacterium on samples from patients with suspected TB would lead to more accurate and timely diagnosis of active TB in many places that currently have barriers to both.

Dataset Overview

The dataset contains images of tuberculosis smears used to detect the presence of acid-fast bacilli in sputum samples. This dataset is a subset of tuberculosis smear images that Wellgen Medical collected from across Asia to train and validate their smear microscopy automated system [8,9]. The slides mostly come from Taiwan, and partially from China, India, and Japan. The slides are digitized using a microscopic scanner and are subdivided into images with the resolution of 2448x2048.

All positive smear images in the dataset come from sputum slides with culture-proven tuberculosis. Many images are generated from a single slide and not all images contain TB bacilli. However only the images with TB bacilli are included in the dataset with the positive label. These bacilli are identified with Wellgen Medical’s AI algorithm and then double checked by two licensed medical technicians.

In the dataset all negative smear images come from sputum from patients with negative culture results.

Our Partners

Established in 2016, Wellgen Medical has developed automated microscopy technology used to detect disease. In order to train their own AI algorithms, Wellgen Medical has collected large amounts of disease samples. Partnering with Nightingale Open Science, Wellgen Medical is sharing their TB smear collection with the broader scientific community in order to fight tuberculosis.

Dataset Details

Versions

This dataset v1: This dataset contains a total of 75,087 microscopic images. These images are taken from sections of TB smears. 71,111 of these images have a negative label and do not contain any TB bacilli. The other 3,976 images have TB bacilli present in the image.

Dataset Summary

| Count | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Images in Dataset | 75,087 | |

| Images with TB Bacilli Present (TB-Postive) | 3,976 | 5.3% |

| Images with no TB Bacilli Present (TB-Negative) | 71,111 | 94.7% |

What’s next for v1.1: The next version of the dataset will include many more images. An estimated 1,000,000 more images will be added to the dataset.

Dataset Schema

Key Variables

Bacilli:

Wellgen Medical has identified images that contain tuberculosis bacilli and those that do not. This dataset contains both those types of images, and those labels can be found in the tb-labels.csv table in the dataset.

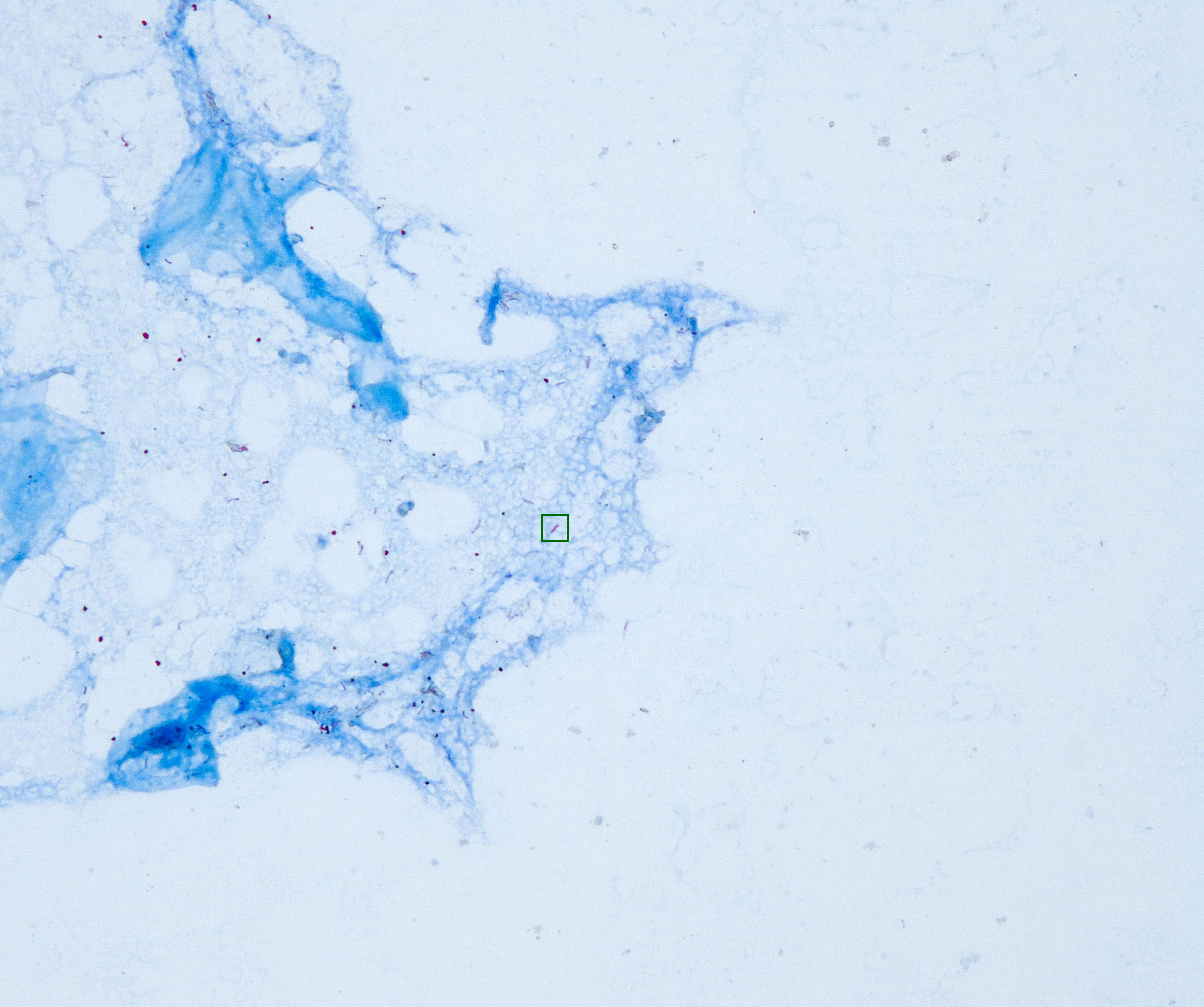

Bacilli are bacteria that are characterized by their rod-like or cylindrical shape. A TB bacillus is tagged with a square in the image below. The images in the dataset, however, are not tagged.

References

- 2021. Global tuberculosis report 2021. World Health Organization, Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240037021

- Philippe Glaziou, Charalambos Sismanidis, and Katherine Floyd. 2021. Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis. In Essential Tuberculosis. Springer International Publishing, 341–348. DOI:http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66703-0_37

- Chandrashekhar T Sreeramareddy, Kishore V Panduru, Joris Menten, and J Van den Ende. 2009. Time delays in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infectious Diseases 9, 1 (June 2009). DOI:http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-9-91

- Dag Gundersen Storla, Solomon Yimer, and Gunnar Aksel Bjune. 2008. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health 8, 1 (January 2008). DOI:http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-15

- Madhukar Pai, Tereza Kasaeva, and Soumya Swaminathan. 2022. Covid-19’s Devastating Effect on Tuberculosis Care — A Path to Recovery. New England Journal of Medicine 386, 16 (April 2022), 1490–1493. DOI:http://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2118145

- Swati Jha, Nazir Ismail, David Clark, James J. Lewis, Shaheed Omar, Andries Dreyer, Violet Chihota, Gavin Churchyard, and David W. Dowdy. 2016. Cost-Effectiveness of Automated Digital Microscopy for Diagnosis of Active Tuberculosis. PLOS ONE 11, 6 (June 2016), e0157554. DOI:http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157554

- Rani Oomman Panicker, Kaushik S. Kalmady, Jeny Rajan, and M.K. Sabu. 2018. Automatic detection of tuberculosis bacilli from microscopic sputum smear images using deep learning methods. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 38, 3 (2018), 691–699. DOI:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbe.2018.05.007

- Hsiao-Chuan Huang, King-Lung Kuo, Mei-Hsin Lo, Hsiao-Yun Chou, and Yusen E. Lin. 2022. Novel TB smear microscopy automation system in detecting acid-fast bacilli for tuberculosis – A multi-center double blind study. Tuberculosis 135, (July 2022), 102212. DOI:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2022.102212

- Hsiao-Ting Fu, Hui-Zin Tu, Herng-Sheng Lee, Yusen Eason Lin, and Che-Wei Lin. 2022. Evaluation of an AI-Based TB AFB Smear Screening System for Laboratory Diagnosis on Routine Practice. Sensors 22, 21 (November 2022), 8497. DOI:http://doi.org/10.3390/s22218497